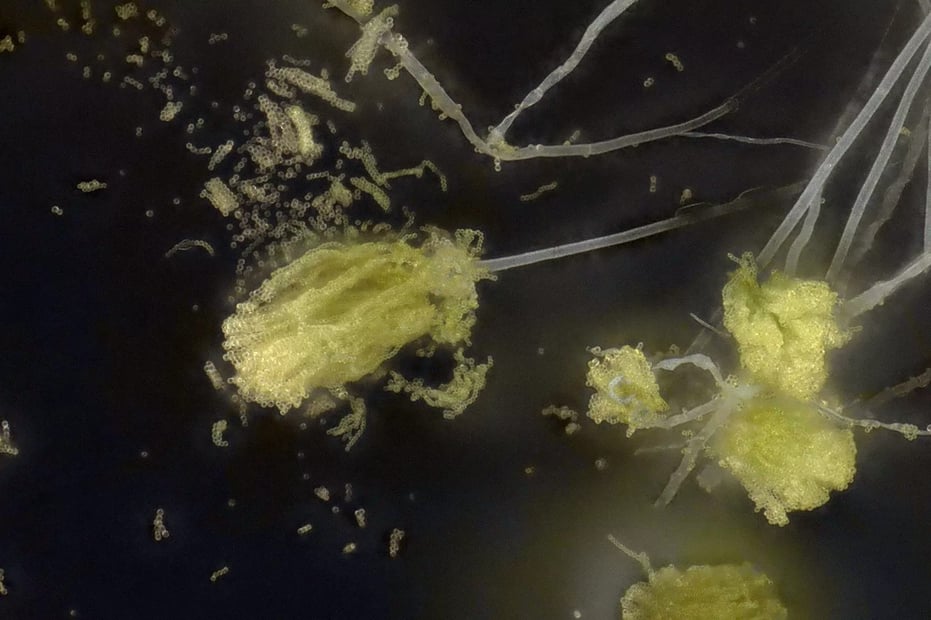

The top image shows a microscopic view of koji mold with numerous spores (Photo courtesy of Harushi Nakajima, Professor at Meiji University)

Professor Harushi Nakajima, a leading researcher in the genetics of microorganisms including koji mold (also known as koji fungus), joins us for this feature. Without koji mold and the koji made from it, there would be no sake, honkaku shochu(single-distillation shochu), miso, or soy sauce. In this installment, he explains the traditional Japanese culture of koji and fermentation.

Expert Commentator: Harushi Nakajima, Professor, Meiji University

Interview & text: Kenji Inoue / Photography: Koichi Mitsui / Composition: Contentsbrain / English Translation: LIBER

Yellow Koji Mold: A Mold Domesticated by the Japanese

In December 2024, “Traditional Knowledge and Skills of Sake-making with Koji Mold in Japan” was officially inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. The use of koji is what sets it apart from spirits like whiskey, gin, and vodka. Koji mold is a type of mold. More specifically, it refers to strains of mold that are beneficial and used in food production.

The main types of koji mold include yellow koji mold, black koji mold, white koji mold, and soy sauce koji mold, each named for its color and use. However, when people say simply “koji mold,” they usually mean yellow koji mold. Yellow koji mold is essentially unique to Japan—it has never been found growing naturally outside the country. Why is that? Because it’s a type of mold that the Japanese discovered and domesticated within Japan.

The scientific name for yellow koji mold is Aspergillus oryzae. All the strains of yellow koji mold identified to date have been discovered at sake breweries, miso producers, and soy sauce makers across Japan. The koji muro⋆1 used to cultivate koji are kept extremely clean, with temperatures maintained around 30℃ and humidity around 60%. Incidentally, if you ask a brewer to see their koji muro, they will rarely agree. That’s because they’re very cautious about letting in outside contaminants.

⋆1 Koji muro (koji room): A special room used to make koji, which plays a vital role in producing sake, miso, and soy sauce. Koji is made by propagating koji mold on steamed grains. When grown on rice, it’s called rice koji; when grown on barley, it becomes barley koji.

Yellow Koji Mold Has Lost the Genes That Produce Mycotoxins—And Can Never Produce Them Again

Aspergillus oryzae, the scientific name for yellow koji mold, is believed to have originated from a mold called Aspergillus flavus. Aspergillus flavus produces aflatoxins—some of the most dangerous and highly carcinogenic mycotoxins known. If domestic pigs are what you get when you tame wild boars, then Aspergillus oryzae is what you get when you domesticate Aspergillus flavus.

Even under an electron microscope, I can’t tell the difference between Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus flavus. However, genetic analysis reveals that in Aspergillus oryzae, the genes responsible for producing mycotoxins have been broken—making it genetically incapable of ever producing them again.

Mycotoxins are produced to eliminate rival organisms competing for limited nutrients. In the wild, Aspergillus oryzae, which doesn’t produce mycotoxins, is at a disadvantage for survival. However, when cultivated by humans in Japan, it doesn’t need mycotoxins. Instead, it has developed multiple nuclei within each spore, which stabilizes its characteristics and amplifies the genes that produce beneficial enzymes like amylase. These traits make it especially well-suited for use in fermented foods.

Japan Commercialized Yellow Koji Mold as Early as 700 Years Ago

How did people in ancient Japan discover, select, and cultivate koji mold? Although it’s a microorganism, koji mold can be seen with the naked eye, touched, and even smelled without a microscope. The Japanese of the past likely used all five senses and went through repeated trial and error to carefully select and refine strains—ultimately cultivating yellow koji mold ideally suited for fermentation.

This development is said to have taken place during the Muromachi period (1336–1573). Across Japan, tane-kojiya⋆2—specialized businesses that sold koji made with pure-cultured yellow koji mold to sake breweries and other producers—began to emerge. These businesses formed trade guilds called Kojiza (Koji Guilds). Records indicate that the Muromachi shogunate protected these guilds—which supplied koji to sake breweries—as a way to secure tax revenue from sake breweries. It was the world’s first biotechnology industry.

⋆2 Tane-kojiya: Businesses that cultivate high-quality koji mold spores for use in the production of miso, soy sauce, sake, shochu, and other fermented products. They collect and commercialize the spores, selling them to brewers and producers. These businesses are also known as moyashi-ya.

The innovation that led to the pure culturing of yellow koji mold was the introduction of kibai, or wood ash. Kibai is ash made by burning deciduous trees such as sawtooth oak. When this is sprinkled onto steamed rice with actively growing yellow koji mold, the pH quickly shifts to alkaline and the surface dries out, killing off most unwanted microbes. Even for yellow koji mold, this sudden change creates a hostile environment. In response, the mold essentially senses, “It’s no longer safe to stay here—we need to leave,” triggering it to produce spores. Tane-kojiya would then collect those spores and sell them as a commercial product.

Characteristics of Black Koji Mold and White Koji Mold Used in Awamori and Honkaku Shochu

Like yellow koji mold, black koji mold is also believed to have been carefully selected and cultivated over a long period from naturally occurring strains.

In sugar-rich environments, yeast and lactic acid bacteria are natural rivals. In sake brewing, the key is to promote the activity of alcohol-fermenting yeast while suppressing lactic acid-fermenting bacteria. Lactic acid bacteria thrive at temperatures between 30℃ and 40℃ but become significantly less active when the temperature drops to about 10℃ to 15℃. Taking advantage of this trait, sake brewing in the days before refrigeration was done during the coldest part of the year—a practice known as kanzukuri (cold-season brewing).

In Kyushu, Okinawa, and other parts of southern Japan—where the climate is warm and kanzukuri is difficult—black koji mold (Aspergillus luchuensis) has been used in place of yellow koji mold for sake production. Black koji mold produces large amounts of citric acid, which is even stronger than lactic acid, helping to suppress the growth of lactic acid bacteria and other unwanted microbes, even in warmer climates.

Yeast is more tolerant of acid than lactic acid bacteria, so alcohol fermentation can still proceed, resulting in a brew with alcohol content. However, the resulting brew was too sour to drink as-is, so it was distilled to extract the alcohol—giving rise to a food culture in which it came to be enjoyed as shochu.

White koji mold is a mutant strain of black koji mold. Its scientific name is Aspergillus luchuensis mut. Kawachii. While it shares the key trait of producing large amounts of citric acid, it causes less staining on work clothes during the brewing process, making it easier to handle. It was isolated by Genichiro Kawachi⋆3—known as the “god of koji fungus.” In the 1950s, it spread throughout the Kyushu region and came to be widely used by many shochu producers.

⋆3 Genichiro Kawachi (1883–1948): A former technical officer at the Ministry of Finance who later became a chemist and entrepreneur. He successfully cultured Kawachi black koji mold in 1910 and discovered Kawachi white koji mold in 1923.

All of these scientific explanations about fermentation came later. Long before microscopes existed, our predecessors built a culture of fermentation through tireless trial and error, relying solely on experience and intuition. Their achievements command deep respect.

Harushi Nakajima

Ph.D. in Agricultural Science from the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, the University of Tokyo. After serving as a research associate at Tokyo Institute of Technology and associate professor at the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, the University of Tokyo, he became associate professor at Meiji University’s School of Agriculture and has held his current position as professor since 2007. Following research on baker’s yeast and organic solvent-tolerant bacteria, he now focuses on hydrophobins—proteins produced by koji mold. He is also active in promoting education in genetic engineering, contributing to food safety policy, and supporting the International Biology Olympiad. A fermentation enthusiast, he favors barley shochu among the many types of honkaku shochu.